Fragmenta Manuscripta

Secular Law

Secular law encompasses all the laws that were put forward by secular institutions, such as the monarchy, the city, or the manor.[1] The Fragmenta Manuscripta collection has fragments that explore secular law through the administration of civil law, the movement of property, and royal orders.

Below are materials from the Fragmenta Manuscripta collection containing general items relating to secular law. The fragments are French and English materials ranging from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries and are primarily secretarial and notarial documents. Keep scrolling for more specific information regarding components of secular law—including the civil law, charters and deeds, receipts, and royal documents.

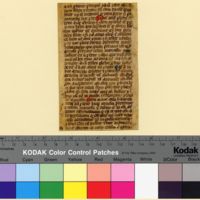

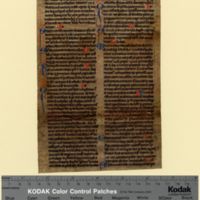

Fragmenta Manuscripta 067r

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Legal treatise

Language: Latin

Location: England?

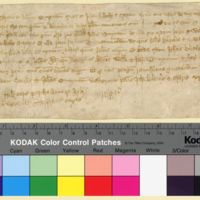

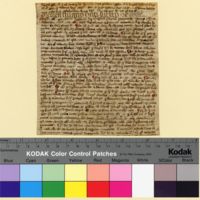

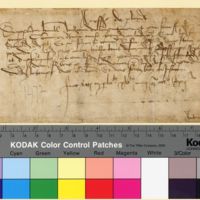

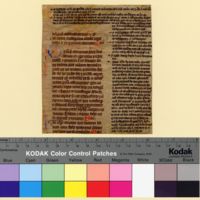

Fragmenta Manuscripta 195r

Date: 1450-1475

Contents: Legal document

Language: French

Location: France

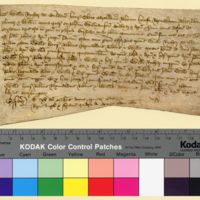

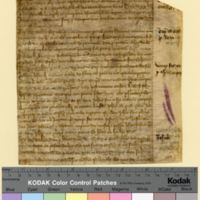

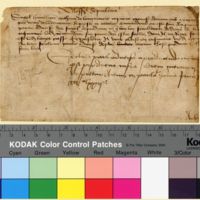

Fragmenta Manuscripta 196r

Date: 1450-1475

Contents: Legal document

Language: French; Latin

Location: France

Civil Law

The civil law is a legal system that emerged in continental Europe after the eleventh century. It was based on the compilation of Roman laws ordered by Emperor Justinian in the sixth century that was lost until its rediscovery in eleventh-century Italy. It is a codified law system that provides precedents for legal matters, including the appropriate punishments for offenses.[2]

Several fragments from the collection contain text from the continental civil law. Conversely, the legal system that developed in England was known as the common law.[3]

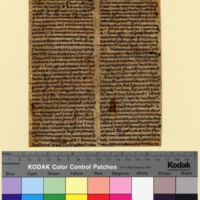

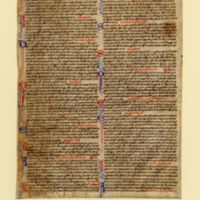

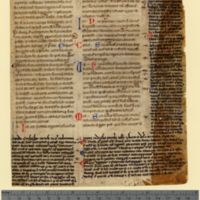

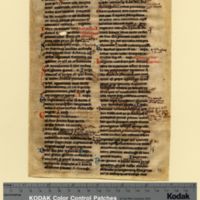

Fragmenta Manuscripta 022

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Civil law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

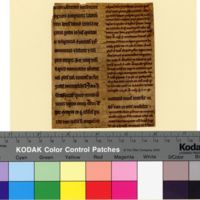

Fragmenta Manuscripta 041

Date: 1200-1250

Contents: Civil law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: Italy; France

Fragmenta Manuscripta 056

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Civil law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England

Fragmenta Manuscripta 113

Date: 1250-1299

Contents: Civil law with gloss

Language: Latin

Location: England?

Charters and Deeds

Charters and deeds are any kind of legal document that concerns property ownership. The property could include land or moveable property like furniture, jewelry, and clothing. The property may also be a rent, right, or privilege (like freedom). Deeds can take on a variety of forms including land grants, leases, marriage contracts, wills, etc. After the thirteenth century, anytime property was moved, a legal deed needed to be written that explicitly stated the granter and the grantee. These deeds were often confirmed with the seals of the grantor for an extra level of authenticity.[4]

The three leaves in the Fragmenta Manuscripta collection all pertain to land. FM 101 involves a dispute about property boundaries. FM 139 is a resumption, which is the action of reassuming possession of lands. Finally, FM 211 is a concession of land.

Fragmenta Manuscripta 211

Date: 1485-1499

Contents: Concession of land

Language: Latin

Location: Italy

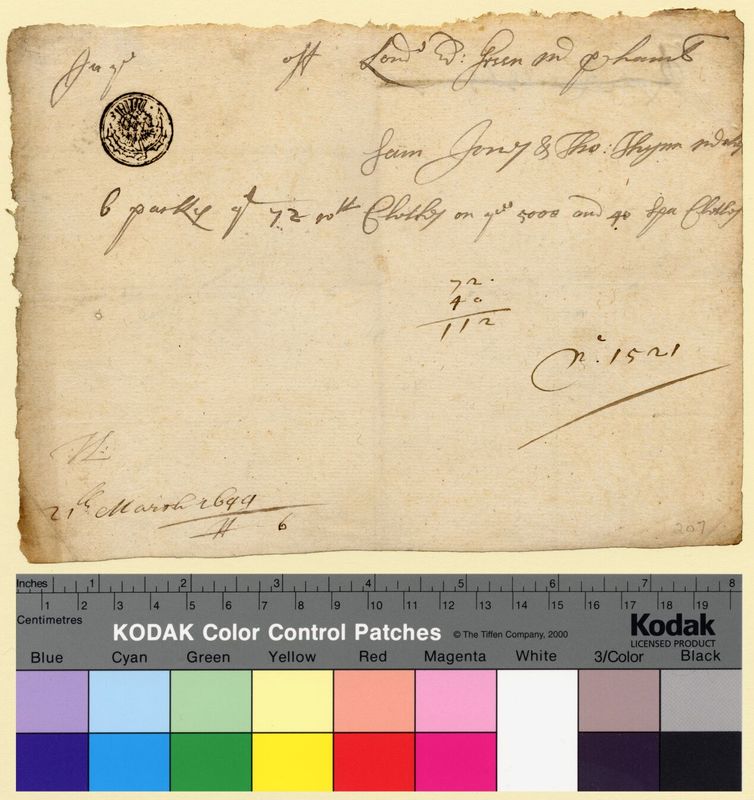

Fragmenta Manuscripta 207

Date: 1640-1660

Contents: Receipt, invoice

Language: English

Location: England

Receipt

Receipts are some of the earliest types of written records that we have. Some 4,000 years ago, the Mesopotamians used clay tablets to record items that were purchased in cuneiform—the very first written language. To learn more about Mesopotamian tablets, see the Cuneiform Tablets housed in our collection.

Receipts provide evidence that transactions and debts had been paid. Different legal entities were formed to manage and regulate administering receipts and exacting payments. In England—where the manuscript fragment was produced (FM 207)—the Exchequer controlled the accounting processes and sheriffs came to collect the taxes from the shires.[5] The penalty for not paying taxes or not having appropriate receipts could be severe. Receipts were typically written in Latin during the Middle Ages and replaced by the vernaculars by the sixteenth century. Receipts would often be kept with the bill, however, since these were written on small pieces of paper or parchment, it is common to find only one or the other. Receipts are part of our daily lives that we do not think much about—but they can reveal a lot about people’s lives and the history of legal systems.[6]

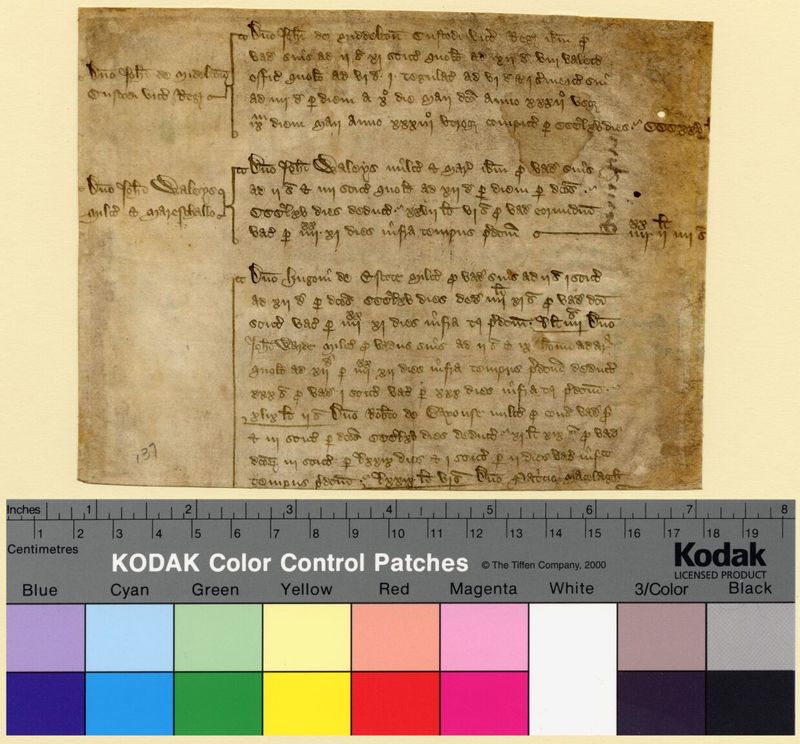

Fragmenta Manuscripta 137

Date: 1300-1399

Contents: Royal document on soldiers serving in France

Language: Latin

Location: England

Royal Documents

The royalty issued their own set of legal documents. Kings and queens granted charters and deeds in their own names, issued proclamations, and from the time of Henry II in England (r. 1154-1189), ruled over the royal court.[7] The Fragmenta Manuscripta collection has one type of legal royal document that pertains to the king’s army in France.

Edward III at War

Edward III, King of England from 1327-1377, inherited the wars of his father and grandfather (Edward II and Edward I). Edward I declared himself king of Scotland and the ensuing conflict is known as the Scottish War of Independence. During the war, the French assisted the Scots in their fight against the English, an alliance which created more hostilities between France and England. The hostile relationship exploded in 1337 when England and France entered into what would become known as the Hundred Years War—even though it was waged over one hundred years, from 1337-1453. These two wars provide enough context to understand why a royal document of Edward III in the Fragmenta Manuscripta collection (FM 137) discusses his soldiers serving in France.

NOTES

[1] Harold J. Berman, Law and Revolution, the Formation of the Western Legal Tradition (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1983), 273.

[2] Berman, Law and Revolution, 123; “The Common Law and Civil Law Traditions,” 2, Law.Berkeley.edu. Accessed June 18, 2020, https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/CommonLawCivilLawTraditions.pdf.

[3] Joseph Dainow. "The Civil Law and the Common Law: Some Points of Comparison," The American Journal of Comparative Law 15, no. 3 (1966): 419-35; “The Common Law and Civil Law Traditions,” Law.Berkeley.edu, accessed June 18, 2020, https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/CommonLawCivilLawTraditions.pdf.

[4] Michael T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066-1307 (Wiley -Blackwell, 2013); “Introduction to Deeds,” Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham, September 2005, https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/deeds/introduction.aspx; "Seals," The National Archives, accessed June 23, 2020, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/seals/.

[5] For more on the exchequer, see Charles Homer Haskins, Norman Institutions (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1918).

[6] “Bills and Receipts,” Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham, last accessed September 7, 2020, https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/accounting/bills.aspx; see also Ellie Jackson, “A Load of Rubbish,” Medieval Manuscripts Blog, The British Library, June 18 2020, https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2020/06/a-load-of-rubbish.html#.

[7] Berman, Law and Revolution, 438-458.

FURTHER READING

- Barrow, G.W.S. Robert Bruce And the Community of the Realm of Scotland. Edinburgh:Edinburgh University Press, 1965.

- Barrow, G.W.S.“Robert I [Robert Bruce] (1274-1329),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. October 4, 2008.

- Froissart, John. Chronicles of England, France, Spain, and the Adjoining Counties. Translated by Thomas Johnes. 2 vols. London: Henry G. Born, 1857.

- MacInnes, Iain A. Scotland’s Second War of Independence: 1332-1357. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: The Boydell Press, 2016.

- Nicholson, Ranald. Scotland: The Later Middle Ages. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1974.